My Two Cents - "Ending the Recession Debate"

11/07/2008

The happy rhetoric of earlier this year has faded. The Treasury Secretary and Fed Chairman are no longer extolling America’s strong economic fundamentals. The media is no longer talking about a soft landing and I haven’t heard the term ‘Goldilocks’ mentioned in what feels like a dog’s age. While our leaders have referred to the ‘challenges’ that we face and the very real possibility of a ‘downturn’, it is very obviously out of vogue to call this reality what it is – a recession. However, history has left us with some pretty good indicators that may be used to either confirm or deny a recession and along with it give us one of the many answers to what is bothering Wall Street these days.

In fact, as recently as yesterday, mainstream financial websites were still entertaining debate as to whether or not the economy is in recession. While it is important to debunk a common misconception that the health of the stock market equals the state of the economy, there are plenty of other dead canaries in the coal mine. So for the benefit of the mainstream press and others still unconvinced, here goes.

Overall Business Conditions

One of the more accurate indicators of recession is the Philadelphia Fed Survey of business conditions. While this survey is generally limited to the Northeast portion of the country, and data is only available from 1968, it has done a marvelous job of nailing recessions (see chart below). Note how each recession since 1968 was preceded by a significant drop in business activity in the Philadelphia District. Despite the serious nature of the current downturn, it is easy to see that things were much worse in the 1975 and 1980 recessions. It is also noteworthy to comment that business conditions have never been this poor as measured by the survey without an official recession. 1996 was the lone period where the measure was significantly below zero without an official recession being declared. The take-home point here is that precipitous drops in the survey have acted as a reliable leading indicator in terms of forecasting recessions. What the survey lacks is the ability to forecast the magnitude of any such recession. The depth and acceleration in the drops in the 1970’s would have portended much more severe economic downturns – even worse than what was experienced - but that proved not to be the case.

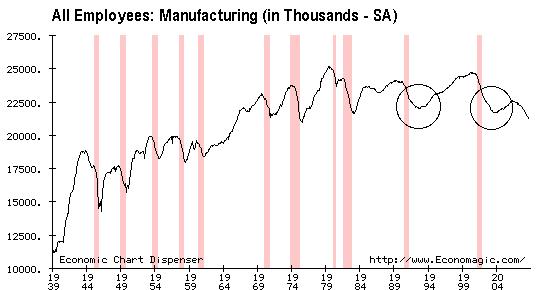

Manufacturing Sector Employment

Another excellent measure of recessions is employment within the goods-producing sector. By way of inference, the below chart also proves one of the tenets of Austrian economic theory – in order to prosper, a nation must first produce. This nagging reality is something that American policymakers would much prefer to forget in favor of building an economy on cheap imported goods then borrowing the money to do so.

In looking at the data from 1939, it is noted that every major drop in manufacturing employment either preceded or corresponded with a recession. What is particularly noteworthy in the above chart is the fact that bottoms in manufacturing employment almost always marked the END of recessions EXCEPT once we got to 1991 and moving forward. This is the same period in time when the inflation metrics started to see major changes and substitution effect and other hedonic adjustments began to emerge. It should also be noted that since 1939 we have never seen a prolonged period of contraction in manufacturing employment without a corresponding recession – until now. In fact, since 2001, we have lost nearly 20% of our manufacturing jobs with only a very minor recession in 2001 being admitted.

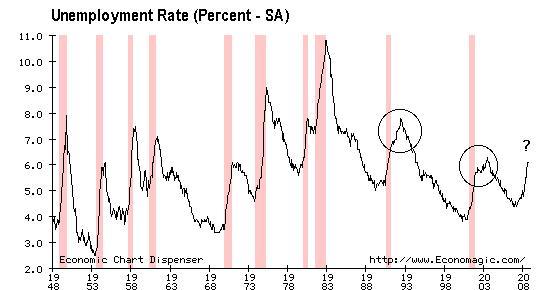

Unemployment (Total)

Closely related to manufacturing sector employment, but worthy of its own analysis is the overall unemployment rate. The linkage between unemployment and economic growth is clear, however, the main reason I chose to include this chart is the disconnects in latter recessions between peaks in unemployment and the duration of the concomitant recessions. Ironically, this dislocation started around the same period during which inflation metrics were changed in favor of more hedonic methodologies. However, unemployment is not adjusted for inflation. Instead, BLS uses a ‘birth-death’ model to predict the number of jobs either created or lost in terms of the startup-shutdown of businesses. Also, drop-offs are no longer calculated in the unemployment rate. If an individual collects for the maximum time allotted and drops off the unemployment rolls it is assumed that they found a job. The measures also fail to properly quantify discouraged workers. Looking at the chart, it is easy to see how significant peaks always corresponded with recessions going back to 1948. In fact, until 2006, the largest prior increase in unemployment without a declared recession was in 1963 when unemployment went from 5.7% to 5.9%. However, during the last 2 years, the unemployment rate has gone from 4.7% to 6.5% and up until recently, we were still hearing about strong fundamentals. A similar occurrence of a jump of this magnitude without a recession simply cannot be found in the data.

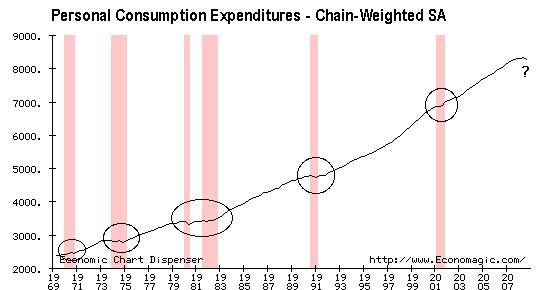

Consumers – The little engine that can’t

Consumers are responsible for upwards of 70% of GDP in America, so it is very logical to expect that how their fiscal health goes, so goes the economy. It is undisputable that this economy cannot prosper or grow in the absence of consumer participation, and I’ll take that one step further and include the consumer’s willingness to take on debt. We have previously demonstrated the high level of correlation between consumer debt and GDP growth.

While the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) graphing doesn’t jump out like some of the other indicators, it becomes very obvious upon closer examination of the areas inside the circles that almost any type of disruption in consumption corresponds with a recession. 1988 and the current period would be two possible examples where this observation failed to play out. However, in the case of the current period, we can observe a period of relative stagnation and then a subsequent DROP in consumption. These observations highlight the fragile relationship between consumption and economic health. Similar to the human body, once homeostasis is disrupted, bad things happen.

It is more and more obvious that as we entered the new century that something changed at a very fundamental level. Since the beginning of the 21st century, America has now undergone 3 major economic dislocations, each one larger than the last. During the majority of this period, the assertions have been that America’s economic fundamentals are strong and that the future is bright. These assertions, more ridiculous by the day, continued until just recently. Whether it is the end of the state of denial or recognition of the fact that we have reached the point of unsustainability remains unclear. What is clear is that the recession is here. The talk should no longer focus on how to prevent it, but on how to get through it without doing any more damage. We are living in a dangerous time. Historically, depressions have ensued not because of inaction, but as the result of too much misguided action. The free market would actually prefer if nothing were done. The free market does not need to be massaged and managed. It is this misunderstanding that has led to the growing cacophony of policy mistakes over the past 75 years. Our economy needs to be cleansed of greed and malinvestment by the free market. Bailouts and other palliative political pandering will only serve to make matters worse.

Until Next Time,

Graham Mehl is a pseudonym. He is not an ‘insider’. He is required to use a pseudonym by the policies of his firm when releasing written work for public consumption. Although not an insider, he is astonishingly bright, having received an MBA with highest honors from the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania. He has also worked as an analyst for hedge funds and one G7 level central bank.

Andy Sutton is a research and freelance Economist. He received international honors for his work in economics at the graduate level and currently teaches high school business. Among his current research work is identifying the line in the sand where economies crumble due to extraneous debt through the use of economic modelling. His focus is also educating young people about the science of Economics using an evidence-based approach.